Can AI Really Read Your Building Plans? AECV-bench Gets a Major Upgrade

Artificial Intelligence

12

min read

January 10, 2026

Remember when we told you that GPT-5 could only identify doors correctly 12% of the time? Three months later, we're back with expanded research, more models, and a deeper dive into what AI can—and can't—do with your architectural drawings.

The results? Some things have improved, and we've uncovered something even more interesting: the massive gap between what AI can read versus what it can understand.

When we released AECV-bench in October, it struck a nerve. Architects and engineers reached out with a consistent message: finally, someone is measuring this instead of just demoing it. So we did what any good researcher would do—we went deeper.

This time, we didn't just count doors. We asked AI to answer questions about drawings. To reason spatially. To extract information from title blocks. To compare elements across a floor plan. The goal: understand not just if AI struggles with drawings, but where and why.

The findings have significant implications for anyone considering AI adoption in AEC workflows—and they challenge some of the bold claims being made by technology vendors in our industry.

TL;DR

10 state-of-the-art multimodal & vision models evaluated across two complementary benchmarks: object counting (120 floor plans) and document QA (192 questions across 21 drawings).

Object counting remains largely unsolved: Even the best model (Gemini 3 Pro) achieves only 51% mean accuracy for counting doors, windows, bedrooms, and toilets.

Document QA shows real promise: Top models reach 0.85 accuracy on drawing-grounded questions—but performance varies wildly by task type.

The capability gradient is clear and consistent: OCR/text extraction (~0.95 accuracy) > comparative reasoning (~0.80) > spatial reasoning (~0.70) > instance counting (~0.40-0.55)

Bottom line: Current AI works well as a document assistant but lacks robust drawing literacy. Symbol-centric tasks like door/window counting remain unreliable for production use without human verification.

Why We Extended AECV-Bench

Our original benchmark focused on a single question: can AI count basic elements in floor plans? The answer was a resounding "not reliably." But counting is just one slice of what architects and engineers do with drawings every day.

Real AEC workflows involve reading title blocks, understanding spatial relationships between rooms, extracting dimensions and scales, comparing areas, identifying circulation paths, and cross-referencing schedules with floor plans. We needed to know: does AI struggle with all drawing tasks, or just the symbol-heavy ones?

The distinction matters enormously for practical deployment. If AI fails at everything related to drawings, that's one conclusion. But if it excels at text-based tasks while struggling with graphical interpretation, we can design workflows that leverage strengths while compensating for weaknesses.

So we built two complementary evaluation pipelines:

Use Case 1: Floor-Plan Object Counting Given a floor plan image, count the doors, windows, bedrooms, and toilets. This is pure symbol recognition and instance enumeration—the foundational capability that underlies quantity takeoffs, egress analysis, and procurement workflows.

Use Case 2: Drawing-Grounded Document QA Given a drawing and a question, provide an answer. Questions span four distinct categories: text extraction (OCR), spatial reasoning, instance counting, and comparative reasoning. This tests broader document comprehension abilities beyond simple counting.

Together, these benchmarks probe the full spectrum of "drawing intelligence"—from basic reading to genuine understanding. The results reveal a clear hierarchy of capabilities that should inform how the AEC industry approaches AI adoption.

The Models We Tested

We evaluated 10 state-of-the-art multimodal and vision-language models, representing the current frontier of AI visual understanding:

Proprietary Models:

Google Gemini 3 Pro

OpenAI GPT-5.2

Anthropic Claude Opus 4.5

xAI Grok 4.1 Fast

Amazon Nova 2 Lite v1

Cohere Command A Vision

Open-Source Models:

Zhipu AI GLM-4.6V

Alibaba Qwen3-VL-8B Instruct (*)

NVIDIA Nemotron Nano 12B v2 VL

Mistral Large 3

(*) Qwen3 is also available in substantially larger variants (e.g., Qwen3 235B A22B Instruct/Thinking). We report results for Qwen3-8B-Instruct because, in our evaluation setting, it offered the best speed–accuracy trade-off; larger variants introduced higher latency without commensurate gains for our tasks.

All models received identical prompts and evaluation protocols through a unified API infrastructure. No cherry-picking of favorable examples. No prompt engineering tricks optimized for specific models. Just a fair, standardized test of drawing comprehension that any practitioner could replicate.

This matters because vendor demonstrations typically show carefully selected examples under ideal conditions. Our benchmark reflects the messy reality of production drawings—varied styles, dense annotations, and the full range of ambiguity that architects and engineers navigate daily.

Use Case 1: Object Counting Results

Given a floor plan image, count the doors, windows, bedrooms, and toilets.

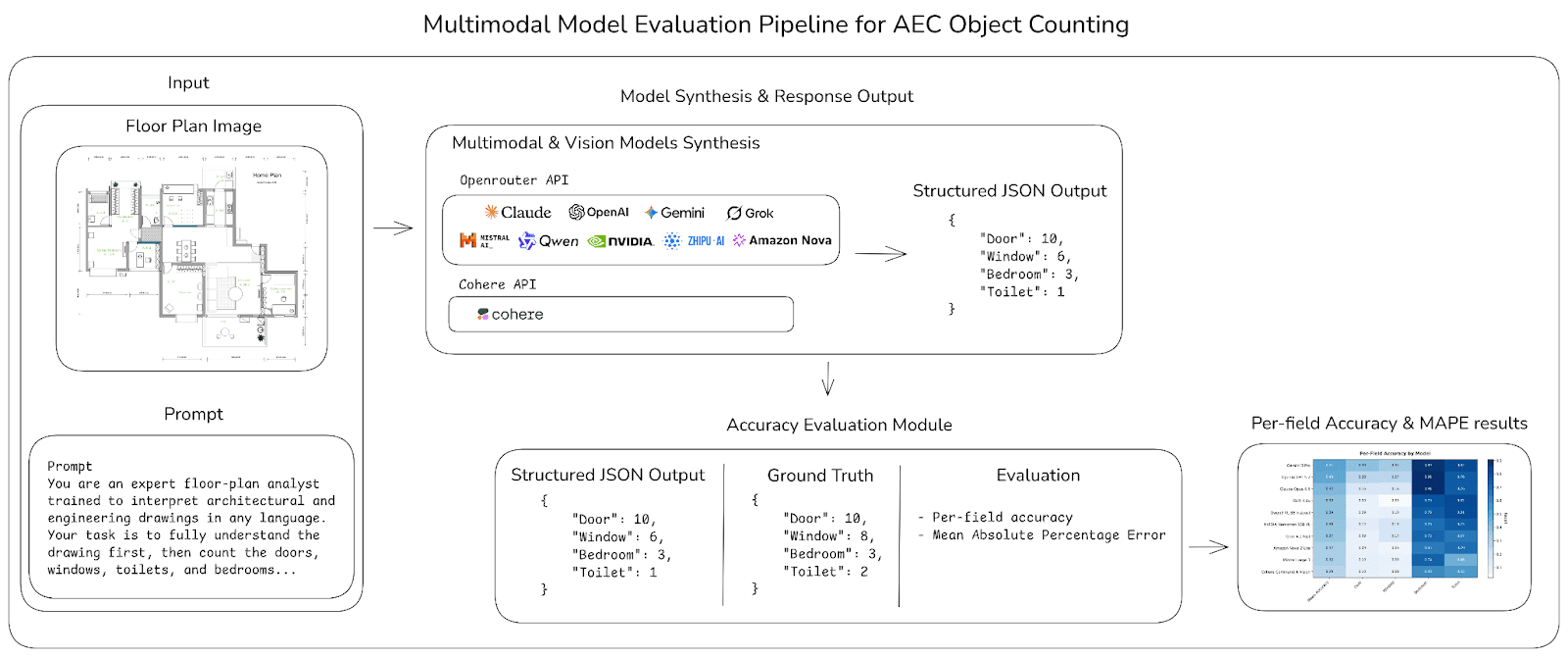

Schematic diagram showing the object counting pipeline: (1) Input floor plan image with structured prompt, (2) Model synthesis through API, (3) Structured JSON output with per-element counts, (4) Accuracy evaluation against ground truth, (5) Heatmap generation for visualization.

The Data

For the object counting benchmark, we curated a dataset of 120 high-quality floor plans from multiple sources: the CubiCasa5K dataset, the CVC-FP dataset, and publicly available drawings collected from the internet. Selection prioritized drawings representative of real AEC plan-reading conditions while remaining legible enough to support consistent annotation and evaluation.

Each floor plan was manually labeled with ground-truth counts for four object classes: doors, windows, bedrooms, and toilets. Ground-truth labels were produced via careful manual review to ensure correctness under common plan ambiguities—doors drawn in different styles, windows represented by varying symbols, and bedrooms identified via room tags or typical layouts when tags are absent.

The Headline Numbers

Let's cut to the chase. Here's how models performed on counting doors, windows, bedrooms, and toilets across all 120 floor plans:

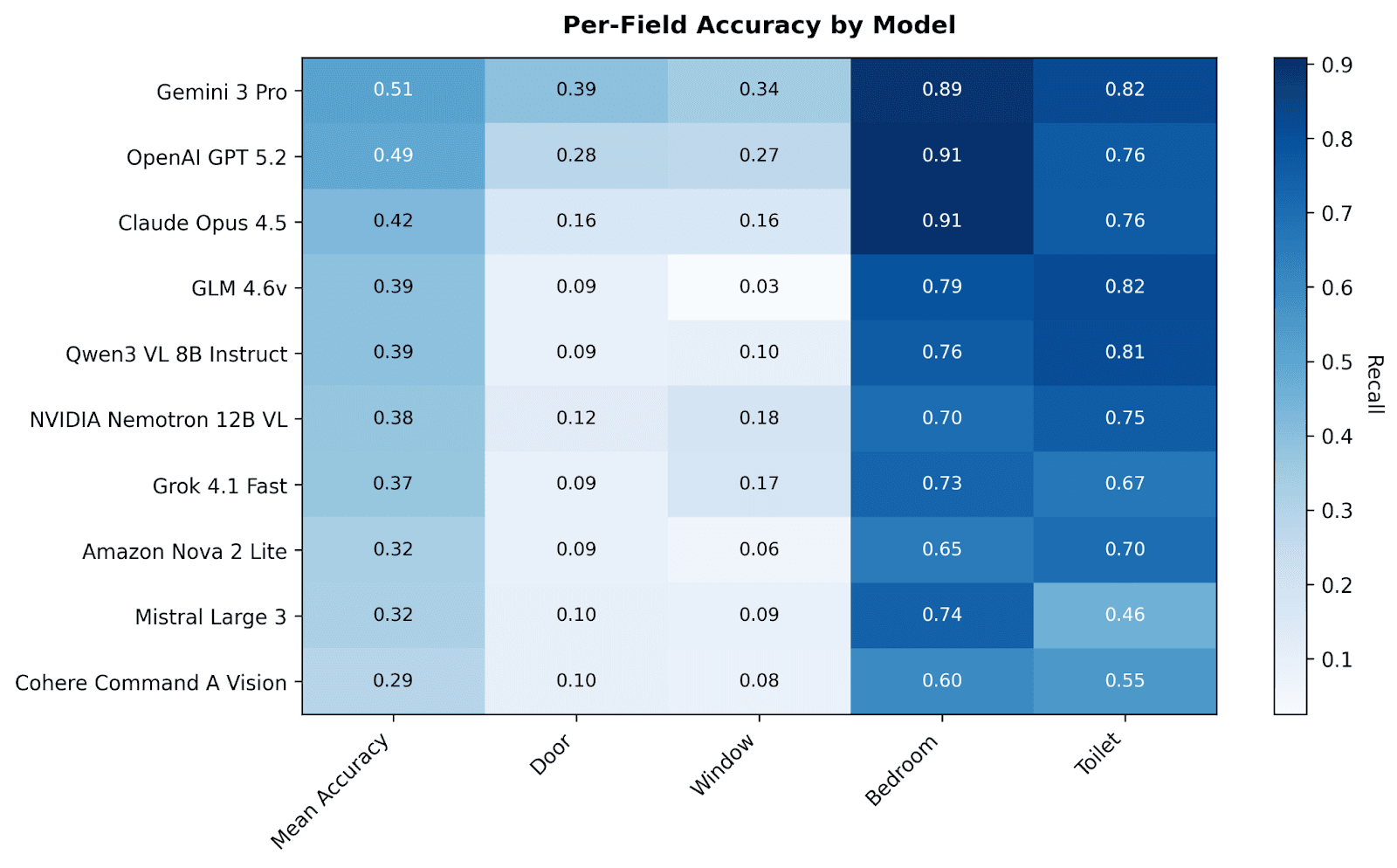

The pattern is unmistakable: bedrooms and toilets are relatively easy; doors and windows are remarkably hard.

Gemini 3 Pro leads the pack with 51% mean accuracy—barely better than a coin flip when averaged across all four element types. GPT-5.2 follows closely at 49%. Claude Opus 4.5 manages 42%. The best open-source model, GLM-4.6V, achieves 39%.

But the per-element breakdown tells the real story:

Element | Best Model | Best Accuracy |

Bedrooms | GPT-5.2 / Claude Opus 4.5 | 91% |

Toilets | Gemini 3 Pro / GLM-4.6V | 82% |

Doors | Gemini 3 Pro | 39% |

Windows | Gemini 3 Pro | 34% |

Why the massive 50+ percentage point gap between bedrooms and windows? The answer reveals a fundamental limitation of current AI approaches to technical drawings.

Bedrooms and toilets are typically labeled with text—"BEDROOM," "WC," "BATH," "Chambre," "Zimmer"—so models can fall back on optical character recognition. They're essentially reading, not interpreting. Doors and windows, by contrast, are conveyed through graphical symbols: arcs showing swing direction, breaks in wall lines, standardized conventions that vary by region, firm, and even individual drafter.

Current AI reads text exceptionally well. It interprets architectural symbols poorly. This distinction has profound implications for what we can and cannot automate.

Error Magnitude: How Wrong Are the Wrong Answers?

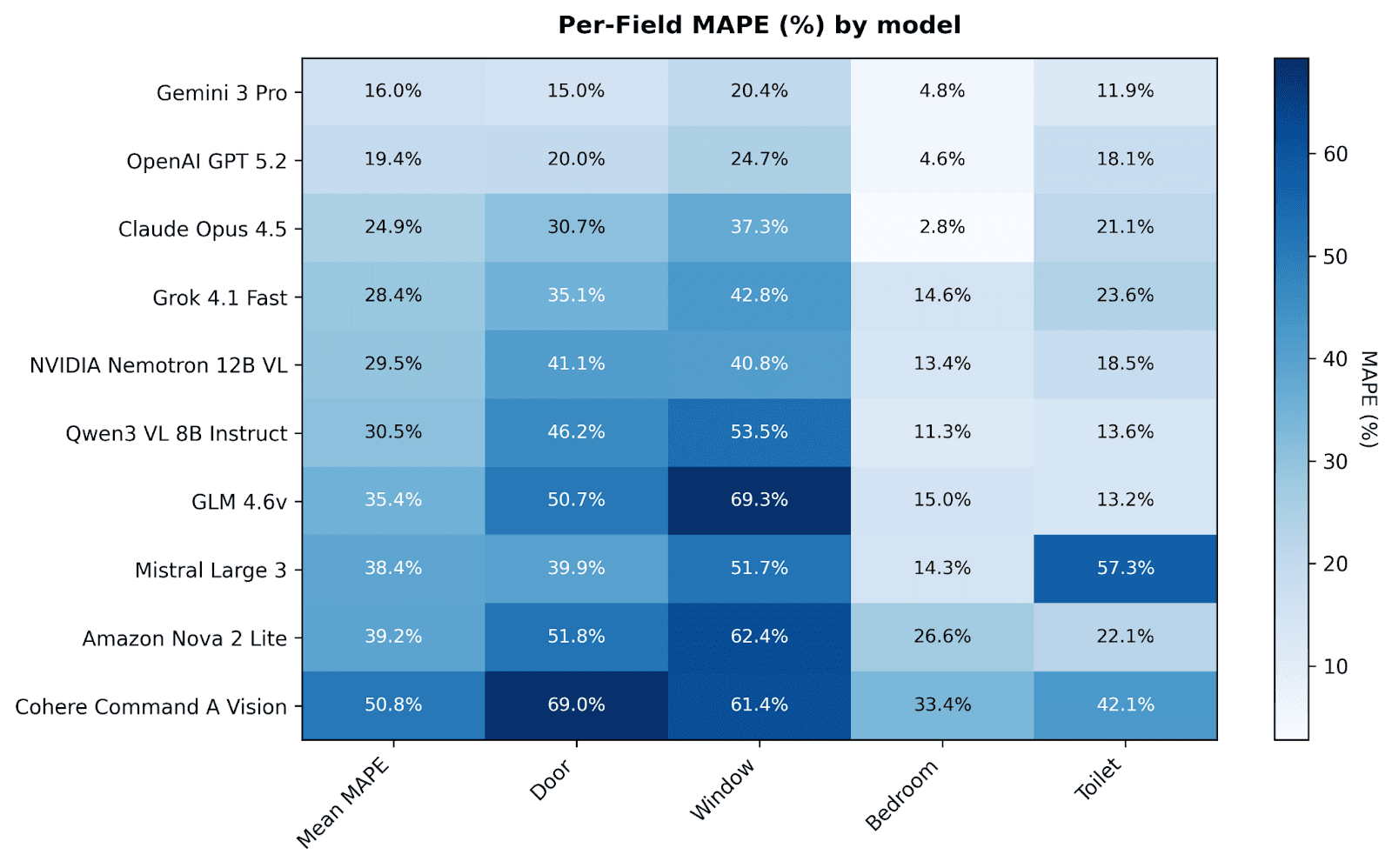

Exact-match accuracy is a harsh metric—if the ground truth is 10 doors and you count 9, you get zero credit. Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) provides a complementary view by capturing how close models get even when they don't hit the exact number:

Gemini 3 Pro achieves 16% mean MAPE—on average, its counts are about 16% off from ground truth. Claude Opus 4.5 shows 24.9% mean MAPE. The worst-performing models exceed 50% MAPE, meaning their counts are off by half or more on average.

A 16% error rate sounds almost acceptable in isolation. But consider what this means in practice:

A floor plan with 10 doors might be counted as 8 or 12

A building with 50 windows could show anywhere from 40 to 60

For fire safety reviews, missing 2 emergency exits could be catastrophic

For security system quotes, adding phantom doors means ordering unnecessary hardware

For energy modeling, a 20% error in window count cascades into meaningless results

The error distribution also varies dramatically by element. Window counts show the highest error rates, sometimes exceeding 60-70% MAPE. Door counts hover around 15-30% for the best performers. This isn't just inaccuracy—at the high end, it's hallucination at a scale that makes output actively misleading rather than merely imprecise.

What's Going Wrong? Failure Mode Analysis

We analyzed the failure patterns across models and identified several systematic issues:

Misinterpreting door swings: The arc that represents a door's swing direction is a convention, not a literal picture. Models frequently confuse these arcs with other curved elements, or miss doors entirely when they're shown without swing arcs (as in some simplified drawings).

Confusing windows with other openings: Glazed doors, curtain walls, skylights, and façade elements all get mixed up with windows. The distinction requires understanding context and conventions that models haven't learned.

Hallucinating fixtures: Models sometimes "see" doors or windows that don't exist, particularly in dense regions where multiple symbols and annotations overlap. This is especially problematic because false positives are harder to catch than false negatives.

Missing instances in cluttered areas: When symbols overlap or annotations crowd a drawing area, accuracy plummets. Real production drawings are rarely as clean as the simplified examples in vendor demos.

Inconsistent handling of multi-leaf doors: Our counting rules specify that each leaf counts separately (a double door = 2 doors). Models inconsistently apply this rule, sometimes counting by opening rather than by leaf.

These aren't random errors—they're systematic failures to understand the graphical language of architectural plans. The same models that achieve near-perfect OCR on the text within these drawings completely fail at interpreting the symbols right next to that text.

Use Case 2: Drawing-Grounded Document QA

Object counting revealed AI's weakness with symbols. But counting is a narrow task. What about the broader range of questions architects and engineers ask about drawings?

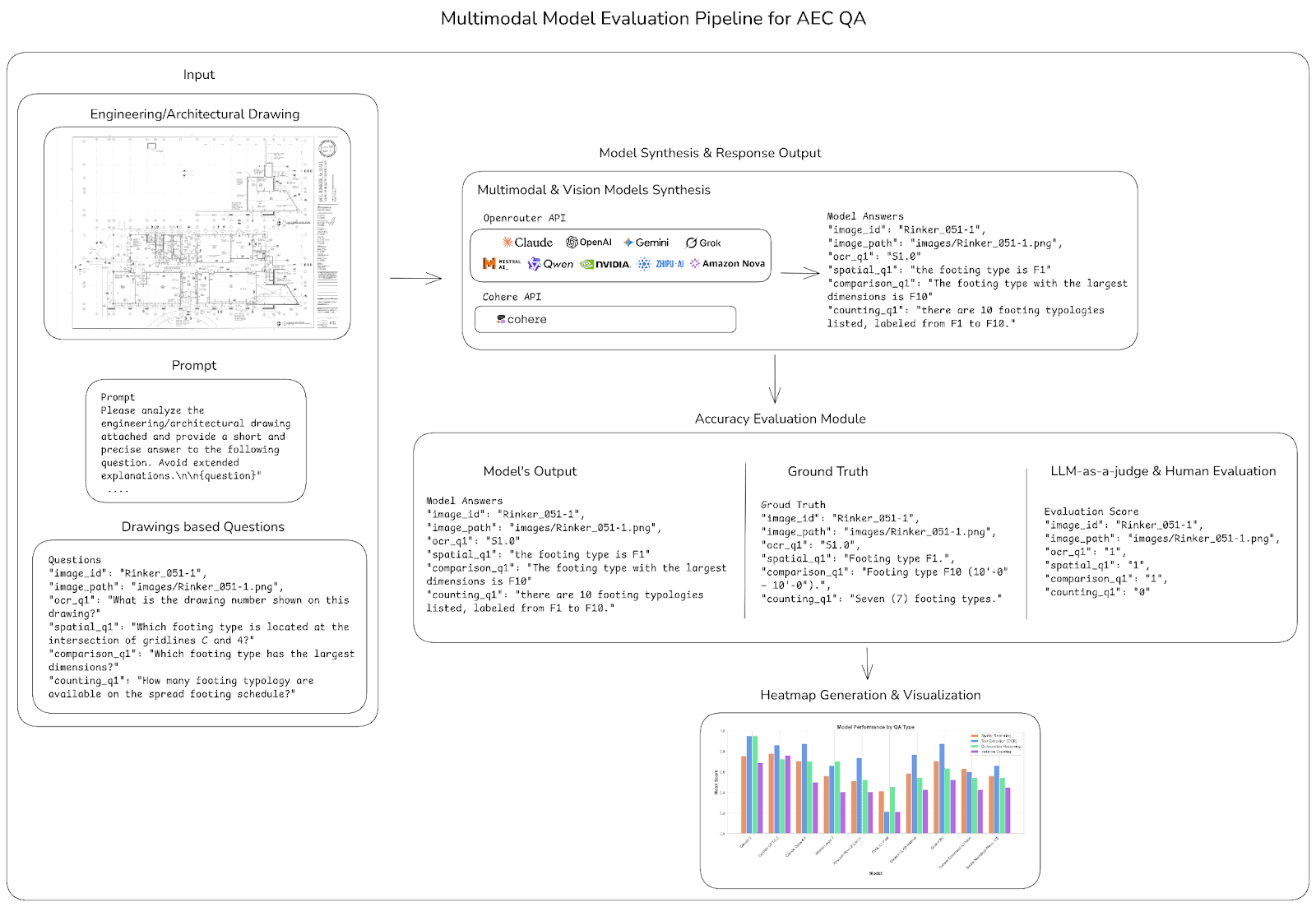

Schematic diagram showing the QA pipeline: (1) Input drawing with category-specific questions, (2) Model synthesis through API, (3) Model answers in structured format, (4) LLM-as-a-Judge evaluation with ground truth, (5) Human adjudication for edge cases, (6) Per-category accuracy visualization.

The QA Dataset

We manually crafted 192 question-answer pairs grounded in a collection of 21 out of the 120 high-quality architectural and engineering drawings. The QA authoring process combined model-assisted generation with rigorous human curation—we used GPT-5 to propose candidate questions, then human reviewers audited these candidates, removed ambiguous items, verified that each question is answerable from the image alone, and authored additional pairs to ensure balanced coverage.

Questions span four distinct categories:

Text Extraction (OCR): Questions that test a model's ability to locate and accurately read labels, values, notes, dimensions, and metadata directly from drawings. Examples: "What is the drawing scale indicated in the title block?" or "What is the room name shown in grid C-4?"

Spatial Reasoning: Questions that require inferring relationships from the drawing rather than reading text directly. Examples: "Which room is adjacent to the main stair?" or "Where is the General Notes section located in the drawing?"

Instance Counting: Questions that test element enumeration within the QA context. Examples: "How many section view callouts are present in the drawing?" or "How many doors provide access to the corridor?"

Comparative Reasoning: Questions requiring comparison across multiple elements. Examples: "Which quadrant has more core access?" or "Which room type has the largest total area?"

Each answer was evaluated using an LLM-as-a-judge pipeline with GPT-4o, producing binary correctness scores. Human adjudication resolved edge cases involving ambiguous drawings, borderline equivalences, and potential judge inconsistencies.

Each answer was evaluated using an LLM-as-a-judge pipeline with GPT-4o, producing binary correctness scores. But automated evaluation alone isn't enough for technical drawings.

Human Adjudication: The Quality Control Layer

Each answer was evaluated using an LLM-as-a-judge pipeline, producing binary correctness scores. But automated evaluation alone isn't enough for technical drawings; we added a human review.

Why We Added Human Review

Here's the thing about architectural drawings: they're messy. Symbols can be unclear. Regions get occluded. And sometimes there's more than one right answer—"Top right corner" and "Northeast quadrant" describe the same spot, but an automated judge might flag one as incorrect.

So we built human adjudication into the pipeline. Reviewers step in for edge cases: ambiguous drawings, borderline-correct answers, and situations where the automated judge and ground truth don't quite align.

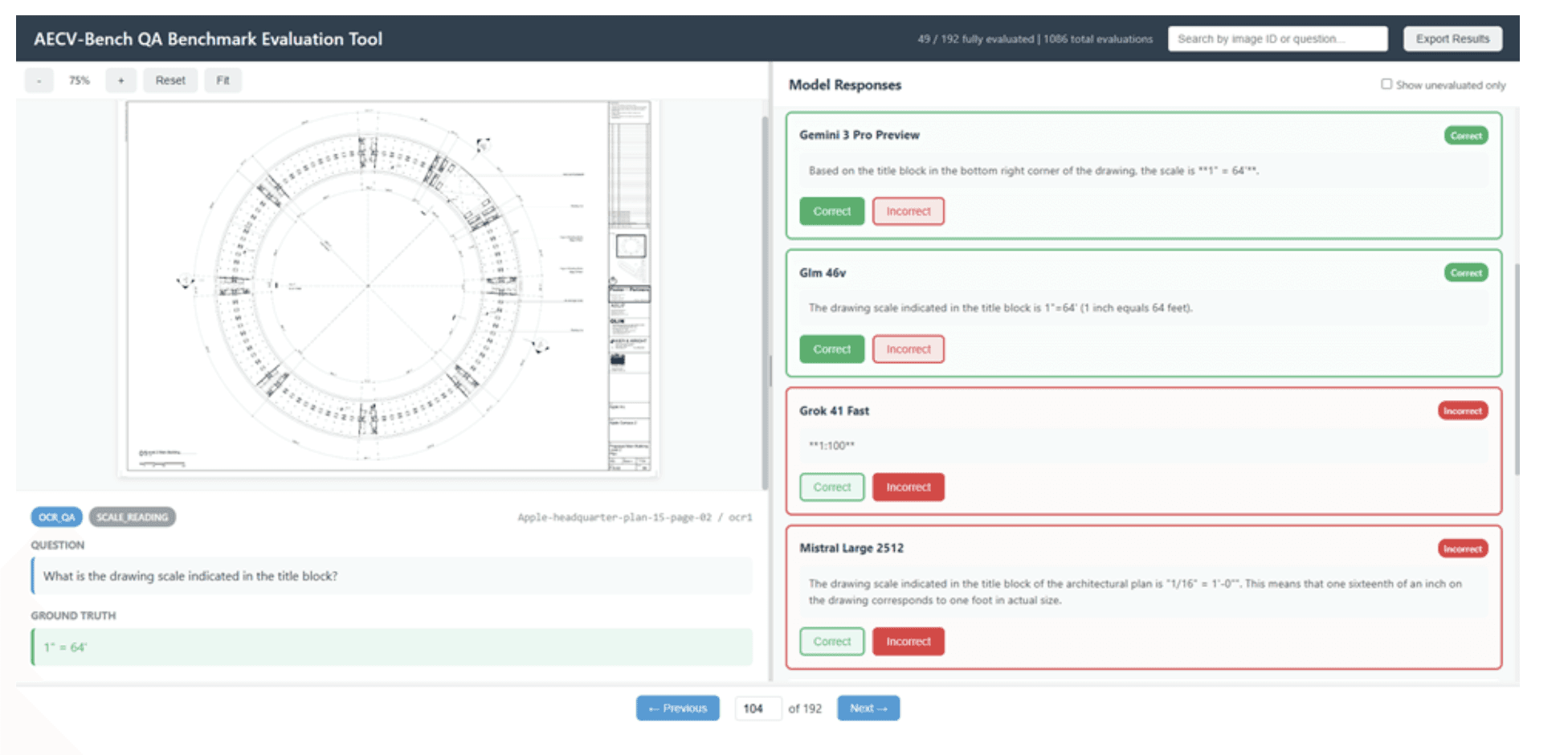

Our web-based evaluation tool showing model responses alongside ground truth, with simple correct/incorrect controls for reviewers.

This human-in-the-loop approach turned out to be essential for making AECV-Bench actually useful. Automated matching mis-scores valid outputs all the time—different wording, formatting variations, unit conversions. Real drawings have genuine ambiguity that no automated system handles well. By having reviewers adjudicate the tough calls and set clear acceptance criteria for each task type, we get consistent scoring that can adapt to different use cases and workflows.

It's the same philosophy we're advocating for AI in AEC more broadly: let machines do the heavy lifting, but keep humans in the loop where expert judgment matters.

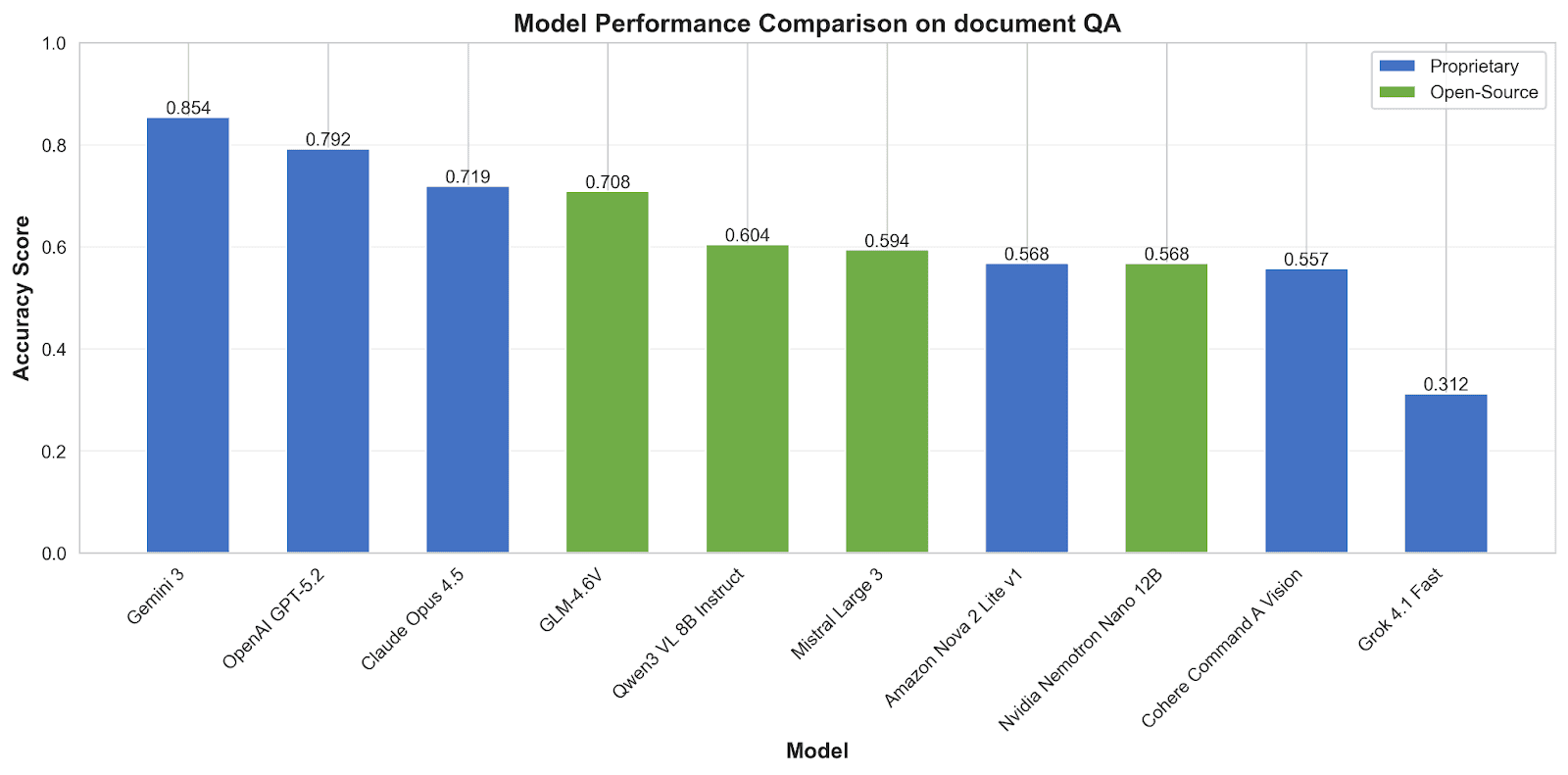

Overall QA Performance

The document QA results show a much more encouraging picture than object counting.

Top models achieve 70-85% accuracy—a meaningful capability level for many practical applications. When AI can rely on reading text and applying reasoning over clearly presented information, it performs respectably.

The 54-percentage-point gap between best (Gemini 3 Pro at 0.854) and worst (Grok 4.1 Fast at 0.312) also highlights that model selection matters enormously. This isn't a mature technology where all options perform similarly.

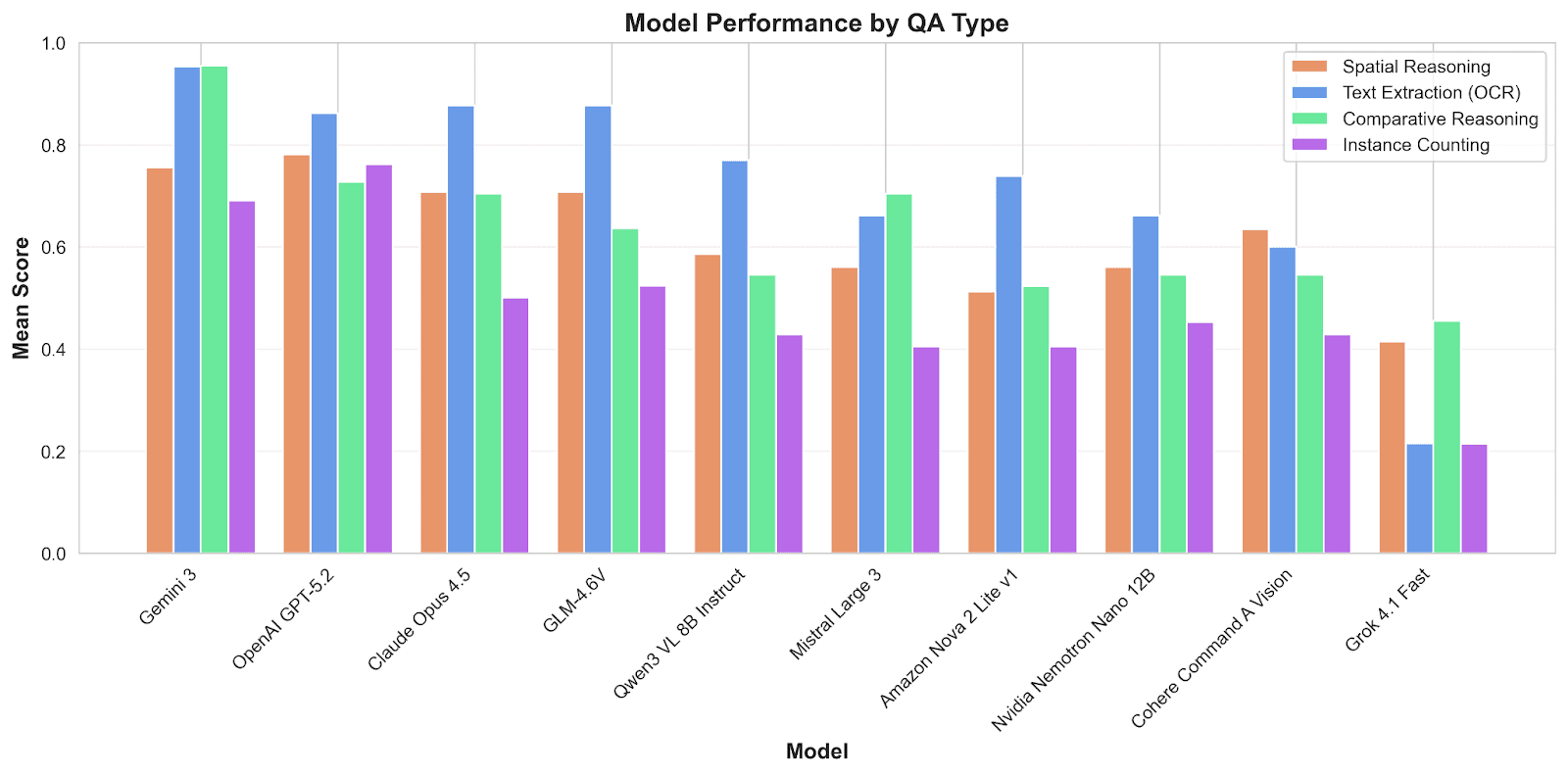

The Capability Gradient: A Consistent Pattern

The per-category breakdown reveals the most important finding of our extended research—a stable capability gradient that holds across all models:

This gradient is remarkably consistent across models of varying capability levels.

OCR is essentially solved for AEC drawings. Models can read title blocks, scales, room labels, dimensions, notes, and revision metadata with high reliability. This is their comfort zone—text recognition is a core capability trained across billions of examples.

Comparative reasoning works when the underlying inputs are reliable. Questions like "which room is largest?" or "which area has more openings?" succeed when models can accurately extract the values being compared. When comparison requires counting (which we know is unreliable), accuracy drops.

Spatial reasoning occupies the middle tier. Answering "where is the stair relative to the elevator?" or "which rooms share a wall with the living room?" requires inferring relationships from graphical layout. This is harder than pure OCR but easier than symbol interpretation.

Instance counting remains the weak link. Whether framed as a standalone task (Use Case 1) or embedded in QA (Use Case 2), asking models to count elements yields consistently poor performance. The symbol interpretation bottleneck persists regardless of context.

The Big Picture: Document Assistant, Not Drawing Expert

Across both benchmarks—120 floor plans for counting and 192 QA pairs for comprehension—a consistent picture emerges:

Current AI works well as a document assistant but lacks robust drawing literacy.

When tasks primarily involve:

Locating and reading text labels

Extracting metadata from title blocks and schedules

Answering questions from clearly labeled regions

Basic spatial navigation with textual reference points

Comparing explicitly stated values

Models perform respectably, often exceeding 80% accuracy. They function as high-throughput readers and organizers of textual information embedded in complex visual artifacts.

But when tasks require:

Interpreting graphical symbols (door swings, window representations)

Accurately counting instances of architectural elements

Understanding CAD conventions that vary by region and firm

Maintaining accuracy across dense, cluttered, or ambiguous drawings

Distinguishing visually similar but semantically different elements

Models fall apart, often achieving 40% accuracy or worse. The graphical language of AEC drawings—evolved over centuries, standardized but variable, dense with domain-specific conventions—remains largely opaque to current vision systems.

This isn't because AI is fundamentally incapable. It's because current models were trained primarily on natural images (photographs) and natural text (documents, web pages), with relatively little exposure to technical drawings. The pretraining distribution doesn't match the deployment domain.

What This Means for the AEC Industry

Where Current AI Can Help Today

Our results strongly support deploying AI as a productivity amplifier around drawings and documents—with appropriate task selection:

Automatic extraction of sheet titles, drawing numbers, revision history, and title block metadata

Retrieval and summarization of notes, specifications, and details relevant to specific spaces or systems

Pre-population of room schedules from labeled tags in floor plans

Linking drawings with associated specifications, change orders, submittals, and RFIs

Search and navigation across large drawing sets using natural language queries

In these workflows, models operate primarily as readers and organizers. Human reviewers can focus on verification and decision-making while AI handles bulk extraction and organization. The time savings are real and meaningful.

Where It Falls Short

Detailed extraction requiring high accuracy remains out of reach. Tasks that demand near-perfect counts—quantity takeoffs, code compliance checking, egress verification, procurement—cannot rely on models achieving 40-75% accuracy on element counting.

A 39% door detection rate makes automated egress analysis impossible. A 34% window identification rate leads to meaningless energy calculations. These aren't "good enough with human review"—they require complete re-verification that often takes longer than manual extraction from scratch.

The trust problem compounds the accuracy problem. If architects must verify every AI output, where's the efficiency gain? Worse, inconsistent errors—missing doors here, hallucinating windows there—make verification harder than starting fresh. You can't efficiently check work when you don't know where the errors are.

A Framework for Adoption Decisions

For AEC firms evaluating AI tools, we suggest a simple framework:

Task Type | AI Reliability | Recommended Approach |

Text extraction (OCR) | High (~95%) | Automate with spot-checking |

Metadata organization | High | Automate fully |

Spatial queries | Moderate (~70%) | Use as draft, verify key items |

Comparative analysis | Moderate-High | Use when based on text, verify if counting-dependent |

Element counting | Low (~40-55%) | Human primary |

Symbol interpretation | Low | Not ready for automation with off-the-shelf AI models |

Organizations that adopt benchmark-driven strategies—selecting tasks based on measured capability rather than vendor claims—are more likely to achieve real productivity gains without compromising safety or quality.

What About Your Drawings?

This benchmark tells you what AI can do on average, across standardized datasets. But your drawings aren't average. They reflect your firm's CAD standards, your consultants' conventions, decades of legacy documentation, and the specific workflows your teams run every day. The gap between benchmark performance and real-world performance can be significant—in either direction. Some firms find their drawings are cleaner than our test set; others discover their legacy documentation triggers failure modes we didn't even test for. That's why we run AECV-Bench on client documents directly.

How the Assessment Works

We take a sample of your actual drawings—floor plans, details, schedules, whatever matters to your workflows—and run them through the same rigorous evaluation pipeline we used for this research. Under NDA, with security controls that satisfy enterprise procurement. What you get back:

Readiness Scorecard — Performance metrics across task categories (OCR, spatial reasoning, counting, comparison) specific to your document types. Not generic benchmarks—your numbers.

Failure Mode Analysis — Where models break on your drawings, mapped to actual workflow risk. Missing fire-rated doors is a different problem than miscounting storage rooms.

Model Recommendations — Which models work for your constraints: cloud-approved vendors, on-premise deployment, open-weight options for air-gapped environments.

Automation Roadmap — Clear guidance on what to automate now, what needs human review, and what to avoid entirely. Plus a pilot plan for the highest-value opportunities. The Process NDA + Scoping — We align on which document types and workflows matter most Benchmark Run — We evaluate your samples using AECV-Bench methodology

Scorecard Delivery — You receive detailed performance data and failure analysis

Roadmap + Implementation Support — We help you act on the findings For firms operating under strict security requirements, we can run the assessment inside your environment with no data leaving your network. The goal isn't a report that sits on a shelf. It's a clear-eyed view of what's possible today—and a practical path to capture that value.

Implications for Model Providers

AECV-Bench exposes a significant domain gap between generic visual understanding and technical drawing requirements. For model providers seeking to serve the AEC market, several implications emerge:

The Pre-training Gap

Strong document QA performance coexisting with weak floor-plan counting reveals that current pretraining regimes heavily emphasize natural images and text, with limited exposure to vector-like artifacts—CAD plans, engineering diagrams, schematics.

Closing this gap will require:

Incorporating large-scale, diverse collections of technical drawings into pretraining corpora

Explicitly modeling line art, symbols, and geometric relationships

Developing hybrid raster-vector representations that capture both appearance and structure

Designing training objectives that favor topological and symbolic consistency

The Interface Opportunity

Many AEC workflows don't need open-ended text responses—they need structured outputs: room inventories, element lists, adjacency graphs, grid mappings. Exposing these as first-class AI outputs would make integration safer and more practical than parsing free-form text.

The Evaluation Imperative

Reporting aggregate "vision scores" or performance on generic captioning datasets is insufficient for regulated industries. AEC stakeholders need:

Task-specific capability breakdowns

Per-domain performance metrics

Clear documentation of failure modes

Explicit guidance on recommended and unsupported use cases

Providers who invest in transparent, domain-specific evaluation will differentiate themselves as enterprises increasingly demand evidence before deployment.

What's Next for AECV-Bench

This extended benchmark is a significant step forward, but it's not the final word. Here's our roadmap:

Industry Partnerships We're establishing collaborations with AEC firms to access production drawings paired with real practitioner queries. Researcher-authored questions are valuable, but evaluation grounded in actual professional workflows yields more actionable insights.

Continuous Leaderboard As new models release, we'll update our public leaderboard. The research community and industry practitioners can track progress over time and identify which providers are actually improving on AEC-specific tasks.

Accessible Tools Current models already deliver meaningful value on OCR and document-centric tasks. We're developing reliable products that enable AEC professionals to leverage these capabilities without requiring technical expertise or infrastructure investment.

Domain-Specific Models We're exploring specialized models targeting the symbol understanding gap. By combining domain-specific pretraining on AEC drawings with architectural knowledge, we aim to close the performance gap between text-based and graphical reasoning.

The Bottom Line

AECV-Bench paints a nuanced picture of multimodal AI for AEC. Existing models are powerful enough to deliver substantial value as document and information assistants around drawings. Their capabilities in OCR, metadata extraction, and text-based reasoning are impressive and improving rapidly.

But they fall short of genuine drawing literacy: understanding symbols, geometry, and code-relevant semantics robustly enough for autonomous decision-making on tasks that matter.

Benchmarks like AECV-Bench make these strengths and limitations visible. For industry, they help align expectations and guide investment toward realistic use cases. For model providers, they indicate where domain-specific innovation is required. For researchers, they open a rich space of problems at the intersection of vision, language, geometry, and formal reasoning.

The question isn't whether AI will transform architecture and construction—it's whether we'll guide that transformation through rigorous evaluation or stumble forward through trial and error.

With billions in construction costs and countless lives affected by what we build, we can't afford to guess.

Get Involved

The full benchmark, evaluation code, and data are available at the Github repo.

More details about methodology can be found in the arXIv paper.

Run the benchmarks on your own models. Contribute additional drawings. Challenge our results. Share your findings—successes and failures alike.

Because honest assessment isn't pessimism—it's the first step toward genuine progress.